The Urban Manufacturing Alliance (UMA) is one of our key strategic partners. The way we think of them is as the modern incarnation of a trade association. Their membership consists of ~500 private and public sector players involved in urban manufacturing across about 150 cities and towns in the United States. Today, most trade associations spend most of their time, money, and energy lobbying at the federal or state level. What makes UMA unique is the fact that it eschews lobbying in favor of a membership-driven approach, where members take it on themselves to codify what is working, leverage their findings it policy recommendations, and then share best practices and policy implications with others in their communities of practice.

Founded by Kate Sofis (SF Made) and Adam Friedman (Pratt Center for Community Development) and headed up by Lee Wellington, the UMA is organized into four communities of practice:

- Workforce Development

- Land Use and Real Estate Development

- Local Branding

- Equity

It’s a holistic view of what it takes to drive the development and support of a robust manufacturing sector inside cities and towns.

Gathering

Each year, UMA hosts a Gathering to bring together its membership in one place for a 2-3 day event. The location of the Gathering is chosen with a great deal of care, so as to be able to make participants aware of what the local community is doing to support urban manufacturing. This year’s Gathering was hosted in Somerville, MA, a town that used to be almost exclusively a working-class enclave. When I attended college in Cambridge, Somerville was the city where graduate students lived due to its proximity to Cambridge and a large number of triple-decker homes that translated into cheap rents. Today, much of Somerville is on the “T” – Boston’s mass transit line – which has brought extreme gentrification to the city. Still, this is a place that remains proud of its roots as a working-class community.

Source: Bike trail near where we stayed in Davis Square, Somerville, MA.

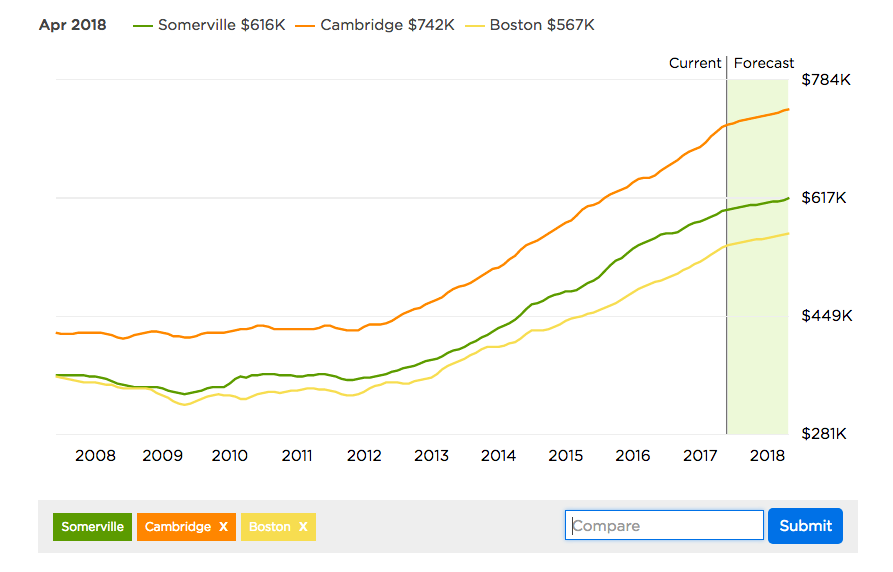

Some 10% of the citizens who live in Somerville are Hispanic according to 2016 Census Data, many without the English-language skills required to work in an office setting. By 2018, the average house is expected to cost $616K in Somerville versus $742K in Cambridge, pricing out many working-class families. Note the acceleration in housing values in Somerville compared with Boston proper, effectively driving out Somerville natives into Boston as well as less transit-friendly suburbs and exurbs.

Source: Zillow data.

Why Attend?

Many of the people who attended the Somerville Gathering were explicit in the fact that they engage with the organization to learn what works in one geography so as to apply that learning to their own city and town. In other words, they were there to steal good ideas. (Stealings never felt so good – one proud participant told us!) You can read more about the UMA in this exclusive case study by Kim-Mai Cutler (formerly a reporter with TechCrunch), which was produced as part of our 2016 book – Maker City: A Practical Guide to Reinventing our Cities.

People came to the Somerville gathering from as far away as California (myself, my business partner Peter Hirshberg) and as close as Somerville itself (Artisan’s Asylum – a Makerspace; The Grommet – an ecommerce site selling goods produced by Makers; NuVu Studio – a school with a strong Maker orientation; Somerville Community Development – workforce development, ) were all in attendance.

For me there were 3 highlight of the meeting and one main take away:

1// Cocktail Party – Manufacturing as a Career Path

The night before the conference proper, Autodesk hosted a cocktail party and panel discussion at its new(ish) space on the Boston Waterfront called BUILD (Build, Innovate, Learn, Design). Housed in the Seaport Innovation District, Autodesk BUILD provides the space and equipment to support work with nearly any material used in the building and infrastructure construction processes—steel, wood, stone, concrete, ceramics, glass, and composites like carbon fiber, which are becoming increasingly important in the industry.

The Autodesk BUILD Space has more than 60 pieces of large-format equipment including six industrial robots, and 11 dedicated workshops for wood, metal fabrication, composites, 3D printing, laser cutting, and large format CNC (Computer Numerical Control) router and waterjet.

All the speakers were excellent, but what blew me away was the poise and coherent point of view put forth by Micah Reid the youngest member of the panel and a late addition (she was subbing in for one of the cofounders of the NuVu Studio, a school for middle schoolers and high schoolers). A senior in high school, Micah is graduating from the NuVu Studio, which you can read about here as part of our book. She will be attending Olin College next September, but intends to pursue manufacturing as a career, something which she would like to see more young people in high school identify as a career path and prepare for much as today they prepare for college. It is not hard to imagine her inventing teleportation and then open sourcing the technology, even if this strategy was to her personal financial detriment.

Another standout from the panel was Amon Millner, Assistant Professor of Computing and Innovation at Olin College. Amon spoke about the importance of making engineering, STEM, and manufacturing as a career path truly representative, which means a greater focus on communities of color for outreach. In particular, he noted that in Germany young people are guided towards two career paths that are equally valued: a vocational path and a professional path. He spoke eloquently about the need to destigmatize the vocational path, that it was the stigma attached to working with one hands that led so many people of color to decide not to pursue the vocational career path. That it was important – instead – to focus on the fact that both paths are equally valuable. Also, to help promote engineering as a career path for people of color.

2//Professor Greg Schrock – Research on Urban Manufacturing

We were familiar Prof. Greg Schrock due to his involvement with Portland Made, where he was part of a team that studied the economic impact of the Maker movement there. You can find the survey here – on the last two pages of the 2014 Report.

More recently, Greg worked with the UMA on a groundbreaking study of the Maker economy in Chicago (IL), New York (NY), Portland (OR).

You can find both an executive summary and the entire report on this site.

This is the first comprehensive report we’ve seen that classifies Makers by type of business, business size, and the like. Among the finding are these:

- Makers generally begin with a focus on products not markets

- A sizable minority of maker-entrepreneurs aspire to remain at small scale

- Maker-entrepreneurs who choose to become manufacturers face significant challenges in scaling up

- Some maker-entrepreneurs, typically those in the hardware and electronics sector, scale up by outsourcing production and finding a global market for their products

- Makers thrive in dense urban environments

- Makers need affordable industrial space but not necessarily Makerspaces

As Greg talked us through his research, he emphasized that there are different profiles of Makers and provided commentary to dimensionalize these findings. Makers tend to not self-identify as entrepreneurs (driven by money) but as more creative types (driven to create a product). Also of importance to Makers: being part of a community of like-minded people and helping their community to be more equitable and inclusive (i.e. social impact).

3// Factory Tour – Somerville

We toured 3 factories in 2 small groups, so I personally got to tour 2 factories. While I thought I would learn the most visiting Formlabs, a maker of 3D printers, in fact this was not the case. It was at the Taza Chocolate factory tour that I had my biggest “Aha” moment as discussed below.

Worker at Taza Chocolate factory preparing cocoa beans as the first step in the manufacturing process

ONE MAIN TAKE AWAY

There was a great deal of discussion of both inclusiveness and scaling at this conference – which makes sense given its theme: Making, Scaling, and Inclusion. That being said, one point of tension was whether the future of manufacturing work will require that workers gain exposure to the modern tools of production or will it be in more artisanal work, where knowledge must be acquired over time and can only be passed down through an extensive apprenticeship. The modern tools of production include computer science, electronics, robotics, CAD/CAM, and CNC tooling … all the things our young[est] panelist at the beginning of this post spoke so elegantly to. Artisanal skills range but can include “old school” vocational skills (e.g. welding) that takes a long time to master as well as instilling “old world” manufacturing techniques to production facilities in the U.S. (e.g. Taza Chocolates).

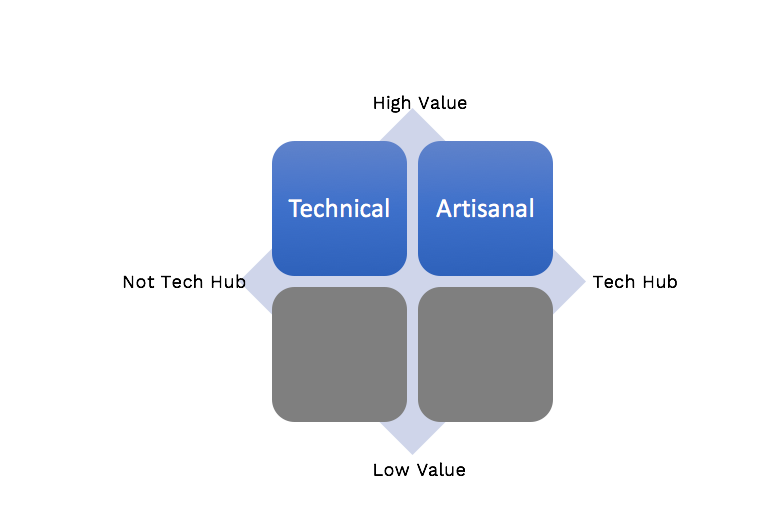

We are starting to think about this tension as a kind of 2 x 2 matrix that looks like this:

What’s important to take away from this matrix is the fact that because the U.S. is a higher priced labor market, it is critical for urban manufacturing firms to go “up the stack” so as to add more value. (U.S. firms cannot compete and win in the low-value quadrants … which is why we grayed them out.)

Going up the stack could happen by leveraging new forms of manufacturing production and/or creating a highly technical product. But of equal value – we think – is manufacturing that is based in artistry either around the production process or the product itself.

With an artisanal product, neither the products nor the production process are ones that can be easily replicated in China or other lower-priced labor markets. Artisanal products often are produced in small batches; to find scale, these kinds of firms need help securing national- and international- distribution as well as generating new forms of demand. That’s where a branded program – to create demand for products made in San Francisco or made in Portland – can come in. Companies like Etsy and The Grommet can also help to create a national market for products made in small batch or by hand.

The beauty of artisanal manufacturing is not just that the products themselves are beautiful; it’s also that the resulting jobs are less susceptible to being automated out of existence. When asked if chocolate making could ever be done by robots, the person leading our tour at the Taza Chocolate factory was emphatic: absolutely not. It takes all one’s senses – olfactory, taste, sight, hearing, touch – to make stone-ground chocolate.

Manufacturing based on technology inputs into the products themselves or process innovation may not be suitable for areas where there is a high density of technology companies. The technology companies tend to soak up all the talent in a way that starves the manufacturing firms of oxygen.

To me, this brings me to the final take away of the two-day UMA Gathering in Somerville. There were many discussions of inclusion at the Gathering. The definition that seemed to resonate with most people is that when establishing an urban manufacturing facility the workforce at the facility should resemble the demographics of the underlying community.

But I personally walked away feeling differently. So many communities in the U.S. – particularly those not located on the two coasts – have been hollowed out by the demise of entire industries. Steel. Coal. Suppliers to the automobile industry, many of which seem to have moved to China as part of globalization of this sector.

As a result of these factors, many cities or town do not necessarily have the right mix of talents to drive a manufacturing renewal. Thus, outsiders are needed to bring a sense of innovation, new skills and talents, new artisanry back into the community. This means that the workforce may not reflect today’s demographics so much as tomorrow’s. This may not be the most “politically correct” definition of inclusion, I grant you. But without an injection of new talent, many urban manufacturing firms will be set up to fail versus to scale. Also required: outside talent to help companies who start out making products at a small scale, to meet the needs of the local market, find national and even international distribution.

RELEVANT LINKS

- NuVu Studio was recently profiled on the U.S. News Maker City hub

- Autodesk BUILD is an example of an industrial Makerspace established in 2016

- Taza Chocolate can be found at your local Whole Foods

Originally published on the Maker City blog